“Expectation is the root of all heartache,” a line often misattributed to Shakespeare, may not belong to the Bard, but it captures a universal truth. Few things steal joy as swiftly as the weight of anticipation. We have expectations from our partners, our parents, our children, our friends, and most cruelly, from ourselves. Films are no exception. When expectations are not met, disappointment is inevitable; when they are, we simply raise the bar higher for the next time. That double-edged sword recently fell on filmmaker Subhash Kapoor, who returned with the third installment of his beloved courtroom franchise Jolly LLB. Sadly, the verdict is not in his favour, not because he lacks talent, but because the franchise has become a prisoner of its own reputation.

The irony is that Jolly LLB built this trap for itself. The 2013 original worked because it was raw and biting, a small-town lawyer’s fight doubling as social satire with teeth. Jolly LLB 2 (2017), with Akshay Kumar stepping in, raised the emotional stakes and married star power with substance. Together, they gave the franchise credibility few commercial courtroom dramas in India had achieved. With Jolly LLB 3, expectations were stratospheric: bring back both Jollys, retain the sharpness of the first film, match the emotional punch of the second, and still deliver popcorn entertainment.

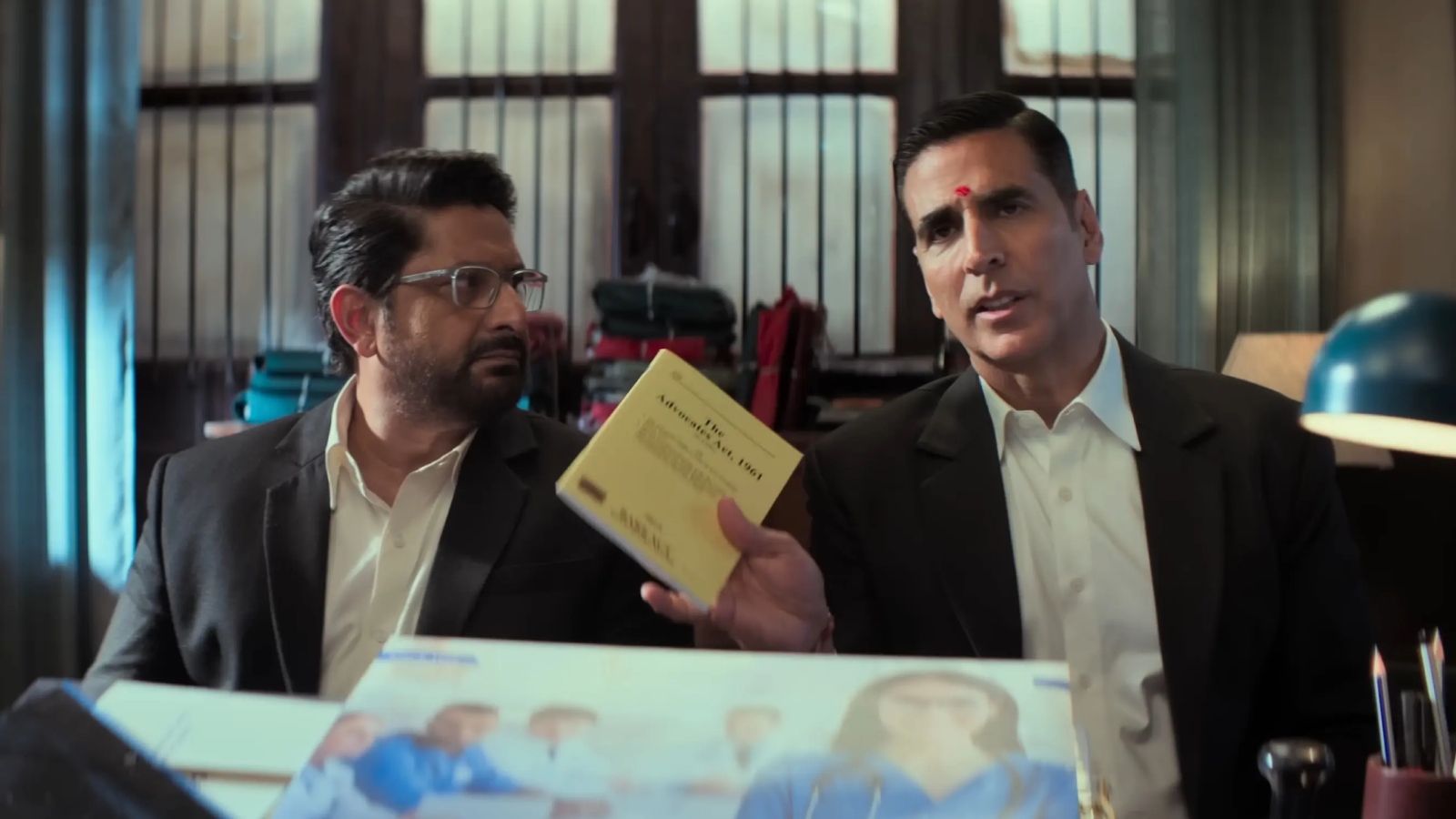

On paper, it was perfect: Arshad Warsi’s scrappy Jagdish Tyagi, Kumar’s starry Jagdishwar Mishra, and Saurabh Shukla’s perpetually exasperated Judge Sunder Lal Tripathi in one frame—the ultimate dream team. But before these men even step into the courtroom, it feels as if their shadows arrive first. The weight of past performances, the success of two beloved films, and the expectations of an audience already convinced of greatness loom so large that by the time the characters themselves walk in, they’re dwarfed by their own legacies. That’s the real burden of Jolly LLB 3: the film doesn’t just have to tell a story, it has to wrestle with the ghosts of everything that came before.

But to figure out where Jolly LLB 3 stumbles, we need to zoom out a little and talk about this larger pattern of movies tripping over their own standards. A lot of podcasters, film critics, and industry folks have been saying it out loud lately: the reason so many big Bollywood tent poles or “pan-India spectacles” aren’t working is simple –– half of them are all talk and no show, and the other half are so obsessed with scaling up their size, bigger stars, fatter budgets, shinier VFX, that they forget to scale up the only thing that really matters: the story, the pen on paper.

Take a recent example. Kantara was made on a shoestring budget of just Rs 16 crores in 2022 and turned into one of the most profitable films in Indian history. Naturally, when the prequel came around, the first thing that got “levelled up” wasn’t the story, but the budget. Over Rs 100 crore, this time. To be clear, the film may well smash records, but judging from the trailer, it felt less like the earthy phenomenon of the first and more like a reminder of what happens when expectations write your script before the filmmaker does.

On the flip side, low expectations can work wonders. Case in point: Saiyaara. A pair of complete newcomers, an indie artist’s song as its title track, a modest romance from YRF at a time when horror comedies were ruling—it walked into theatres wearing a “low expectations” badge. And that became its superpower. With no baggage to carry, it surprised everyone, pulled in audiences, and became a word-of-mouth hit. It gave producers hope, exhibitors smiles, and, Anupam Kher, depression.

Jolly LLB 3 had no such luxury. It didn’t need to be a Saiyaara, and it didn’t have to pull a Kantara. All it had to do was stick to its roots: a sharp, funny courtroom dramedy. Instead, most of the drama and comedy unfold outside the courtroom. With Warsi, Kumar, and Shukla in hand, it’s no surprise Kapoor leans heavily on callbacks—but this time, the humour feels staged. Where the first two films found jokes organically in situations, LLB 3 too often bends situations to set up punchlines. It’s as if Kapoor felt obligated to inject “jollyness” (pun intended) at every turn.

Story continues below this ad

Perhaps the bigger problem is the film’s lack of faith in its audience. Instead of letting history speak for itself, it spoon-feeds reminders. In one scene, Judge Tripathi calls both Jollys into his chamber. By sheer history, he has every reason to groan about these two being thorns in his side. Instead, the exchange turns into a clumsy recap—reminding the characters, and us, of their past antics as if we’ve forgotten. In the age of OTT, no one forgets what happened ten or fifteen years ago. Audiences are sharper, quicker, and far less tolerant of handholding.

The tragedy of Jolly LLB 3 is not that it’s unwatchable. Warsi brings warmth, Kumar brings charisma, Shukla brings gravitas. The problem is that the film buckles under the expectations it built for itself. The humour feels forced, the message doesn’t cut as deep, and the story never escapes the long shadow of its own name. Sometimes, the heaviest burden a film carries is not its script, but its legacy.

![https://primexbt.investments/start_trading/?cxd=459_549985&pid=459&promo=[afp7]&type=IB](https://tradinghow.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/primexbt-markets-e1738588646201.jpg)

![https://primexbt.investments/start_trading/?cxd=459_549985&pid=459&promo=[afp7]&type=IB](https://tradinghow.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/primexbt-markets.jpg)

![https://primexbt.investments/start_trading/?cxd=459_549985&pid=459&promo=[afp7]&type=IB](https://tradinghow.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/PrimeXBT-Trading.jpg)